what step did rosevelt take to deal with the 1902 coal strike

The Coal strike of 1902 (also known as the anthracite coal strike)[1] [two] was a strike by the United Mine Workers of America in the anthracite coalfields of eastern Pennsylvania. Miners striked for higher wages, shorter workdays, and the recognition of their union. The strike threatened to close downwardly the winter fuel supply to major American cities. At that fourth dimension, residences were typically heated with anthracite or "hard" coal, which produces higher rut value and less fume than "soft" or bituminous coal.

The strike never resumed, every bit the miners received a ten percent wage increase and reduced workdays from ten to ix hours; the owners got a higher price for coal and did non recognize the trade marriage as a bargaining agent. It was the start labor dispute in which the U.S. federal government and President Theodore Roosevelt intervened as a neutral arbitrator.[ commendation needed ]

The 1899 and 1900 strikes [edit]

The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) had won a sweeping victory in the 1897 strike by the soft-coal (bituminous coal) miners in the Midwest, winning significant wage increases. Information technology grew from 10,000 to 115,000 members. A number of small strikes took place in the anthracite district from 1899 to 1901, by which the labor union gained experience and unionized more than workers. The 1899 strike in Nanticoke, Pennsylvania, demonstrated that the unions could win a strike directed against a subsidiary of 1 of the big railroads.[3]

Coal miners in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, in 1900.

It hoped to make similar gains in 1900, but constitute the operators, who had established an oligopoly through concentration of buying later on desperate fluctuations in the market for anthracite, to exist far more determined opponents than it had anticipated. The owners refused to meet or to arbitrate with the union; the spousal relationship struck on September 17, 1900, with results that surprised even the union, as miners of all different nationalities and ethnicities walked out in support of the matrimony.

Republican Party Senator Mark Hanna from Ohio, himself an owner of bituminous coal mines (non involved in the strike), sought to resolve the strike as it occurred less than two months earlier the presidential election. He worked through the National Civic Federation which brought labor and capital letter representatives together. Relying on J. P. Morgan to convey his message to the industry that a strike would hurt the reelection of Republican William McKinley, Hanna convinced the owners to concede a wage increase and grievance process to the strikers. The industry refused, on the other hand, to formally recognize the UMWA equally the representative of the workers. The spousal relationship declared victory and dropped its demand for union recognition.[iv]

The black coal strike [edit]

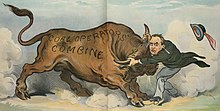

John Mitchell, President of the UMWA, takes the bull (coal trusts) by the horns.

The issues that led to the strike of 1900 were only as pressing in 1902: the matrimony wanted recognition and a degree of control over the manufacture. The industry, still smarting from its concessions in 1900, opposed whatever federal role. The 150,000 miners wanted their weekly pay envelope. Tens of millions of city dwellers needed coal to heat their homes.

John Mitchell, President of the UMWA, proposed mediation through the National Civic Federation, and so a body of relatively progressive employers committed to collective bargaining equally a means of resolving labor disputes. In the alternative, Mitchell proposed that a committee of eminent clergymen report on weather condition in the coalfields. George Baer, President of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, one of the leading employers in the industry, brushed bated both proposals dismissively:

Anthracite mining is a business, and non a religious, sentimental, or academic proposition.... I could non if I would delegate this business direction to nonetheless highly a respectable trunk as the Borough Federation, nor tin can I telephone call to my help . . . the eminent prelates yous accept named.[v]

On May 12, 1902, the anthracite miners voting in Scranton, Pennsylvania, went out on strike. The maintenance employees, who had much steadier jobs and did not face up the special dangers of underground work, walked out on June two. The matrimony had the support of roughly fourscore pct of the workers in this area, or more than 100,000 strikers. Some 30,000 left the region, many headed for Midwestern bituminous mines; 10,000 men returned to Europe.[half-dozen] The strike presently produced threats of violence between the strikers on 1 side and strikebreakers, the Pennsylvania National Baby-sit, local police, and hired detective agencies on the other.[seven]

Federal intervention [edit]

On June eight, President Theodore Roosevelt asked his Commissioner of Labor, Carroll D. Wright, to investigate the strike. Wright investigated and proposed reforms that acknowledged each side'south position, recommending a nine-hour day on an experimental footing and express collective bargaining. Roosevelt chose not to release the written report, for fear of appearing to side with the marriage.

Theodore Roosevelt teaches the childish coal barons a lesson; 1902 cartoon by Charles Lederer

The owners, for their part, refused to negotiate with the spousal relationship. As George Baer wrote when urged to brand concessions to the strikers and their marriage, the "rights and interests of the laboring man will be protected and cared for—not by the labor agitators, simply by the Christian men to whom God in His infinite wisdom has given the control of the property interests of the country."[viii] The union used this letter of the alphabet to sway public opinion in favor of the strike.

Roosevelt wanted to intervene, but he was told past his Attorney General, Philander Knox, that he had no dominance to practise and then. Hanna and many others in the Republican Political party were also concerned virtually the political implications if the strike dragged on into wintertime, when the need for anthracite was greatest. As Roosevelt told Hanna, "A coal famine in the winter is an ugly matter and I fear nosotros shall encounter terrible suffering and grave disaster."[9]

Roosevelt convened a conference of representatives of government, labor, and management on October three, 1902. The union considered the mere holding of a coming together to be tantamount to union recognition and took a conciliatory tone. The owners told Roosevelt that strikers had killed over 20 men and that he should use the power of government "to protect the man who wants to piece of work, and his married woman and children when at work."[10] With proper protection, the owner said that they would produce enough coal to stop the fuel shortage; they refused to enter into any negotiations with the matrimony. The governor sent in the National Guard, who protected the mines and the minority of men still working. Roosevelt attempted to persuade the union to finish the strike with a promise that he would create a committee to study the causes of the strike and propose a solution, which Roosevelt promised to support with all of the say-so of his role. Mitchell refused and his membership endorsed his conclusion by a about unanimous vote.[10]

The economics of coal revolved effectually two factors: most of the price of production was wages for miners, and if the supply brutal, the price would shoot up. In an age earlier the use of oil and electricity, there were no good substitutes. Profits were low in 1902 because of an over supply; therefore the owners welcomed a moderately long strike. They had huge stockpiles which increased daily in value. It was illegal for the owners to conspire to close down product, but not so if the miners went on strike. The owners welcomed the strike, but they adamantly refused to recognize the union, considering they feared the union would command the coal industry by manipulating strikes.[xi]

Roosevelt continued to try to build support for a mediated solution, persuading former president Grover Cleveland to join the committee he was creating. He also considered nationalizing the mines under the leadership of John M. Schofield.[12] This would put the U.S. Ground forces in control of the coalfields[xiii] [14] to "run the mines every bit a receiver", Roosevelt wrote.[15]

J.P. Morgan intervenes [edit]

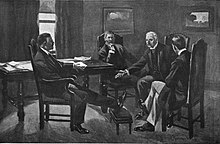

Theodore Roosevelt and J.P. Morgan accept a meeting where they agree on a resolution for the strike.

J.P. Morgan, the dominant figure in American finance, had played a role in resolving the 1900 strike. He was deeply involved in this strike as well: his interests included the Reading Railroad, ane of the largest employers of miners. He had installed George Baer, who spoke for the manufacture throughout the strike, as the head of the railroad.[16]

At the urging of Secretary of War Elihu Root, Morgan came up with some other compromise proposal that provided for arbitration, while giving the manufacture the right to deny that it was bargaining with the union past directing that each employer and its employees communicate directly with the committee. The employers agreed on the condition that the five members be a military engineer, a mining engineer, a judge, an expert in the coal business, and an "eminent sociologist". The employers were willing to have a union leader as the "eminent sociologist," so Roosevelt named E. Eastward. Clark, head of the railway conductors' union, every bit the "eminent sociologist." After Catholic leaders exerted pressure, he added a 6th member, Cosmic bishop John Lancaster Spalding, and Commissioner Wright as the seventh member.[17]

Anthracite Coal Strike Commission [edit]

The anthracite strike ended, after 163 days, on October 23, 1902. The commissioners began work the side by side day, so spent a week touring the coal regions. Wright used the staff of the Department of Labor to collect data about the cost of living in the coalfields.

Committee appointed by Roosevelt to resolve the dispute, photographed past William H. Rau

The commissioners held hearings in Scranton over the next iii months, taking testimony from 558 witnesses, including 240 for the striking miners, 153 for nonunion mineworkers, 154 for the operators, and eleven called by the Commission itself. Baer fabricated the closing arguments for the coal operators, while lawyer Clarence Darrow closed for the workers.

Although the commissioners heard some evidence of terrible atmospheric condition, they concluded that the "moving spectacle of horrors" represented but a minor number of cases. More often than not, social weather condition in mine communities were institute to be good, and miners were judged as just partly justified in their claim that annual earnings were non sufficient "to maintain an American standard of living."

Baer said in his endmost arguments, "These men don't endure. Why, hell, half of them don't fifty-fifty speak English".[xviii] Darrow, for his part, summed upwards the pages of testimony of mistreatment he had obtained in the soaring rhetoric for which he was famous: "Nosotros are working for democracy, for humanity, for the future, for the day volition come also late for u.s. to see it or know information technology or receive its benefits, but which will come, and will remember our struggles, our triumphs, our defeats, and the words which we spake."[19]

In the cease, however, the rhetoric of both sides made piddling difference to the Commission, which split the deviation betwixt mineworkers and mine owners. The miners asked for 20% wage increases, and near were given a 10% increment. The miners had asked for an 8-hour day and were awarded a ix-60 minutes day instead of the standard x hours and so prevailing. While the operators refused to recognize the United Mine Workers, they were required to agree to a six-man arbitration board, made up of equal numbers of labor and direction representatives, with the ability to settle labor disputes. Mitchell considered that de facto recognition and chosen it a victory.[20]

Backwash of the strike [edit]

John Mitchell wrote that eight men died during the v months, "three or iv" of them strikers or sympathizers. [21] During the extensive arbitration testimony, later on company owners fabricated claims that the strikers had killed 21 men, Mitchell disagreed strongly and offered to resign his position if they could name the men and testify proof.[22]

The two sides were supposed to listen to expert testimony and come to a friendly agreement; cartoon from the Cleveland Dealer

The get-go casualty occurred July 1. An immigrant striker named Anthony Giuseppe was constitute fatally shot well-nigh a Lehigh Valley Coal Visitor colliery in Old Forge; it was thought the Coal and Fe Police guarding the site shot blindly through a fence.[23] Street fighting in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania on July thirty between a mob of five,000 striking miners versus constabulary resulted in the beating death of Joseph Beddall, a merchant and the brother of the deputy sheriff.[24] Contemporary reporting describes three other deaths and widespread shooting injuries among strikers and Shenandoah constabulary.[25] On Oct 9, a striker named William Durham was shot and killed in Brownsville, Pennsylvania, near Shenandoah. He'd been loitering most the half-dynamited house of a non-union worker and disobeyed an social club to halt.[26] The legality of that killing nether martial law became a instance, Commonwealth v. Shortall, that was taken to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

The behavior and private role of the Coal and Iron Police force during the strike led to the germination of the Pennsylvania Country Police, on May 2, 1905 as Senate Nib 278 was signed into law past Governor Samuel W. Pennypacker.[27] The two forces operated in parallel until 1931.

Organized labor celebrated the outcome every bit a victory for the UMWA and American Federation of Labor unions generally. Membership in other unions soared, as moderates argued they could produce concrete benefits for workers much sooner than radical Socialists who planned to overthrow commercialism in the future. Mitchell proved his leadership skills and mastery of the problems of ethnic, skill, and regional divisions that had long plagued the union in the anthracite region. Past contrast the strikes of the radical Western Federation of Miners in the W often turned into full-scale warfare between strikers and both employers and the ceremonious and military machine authorities. This strike was successfully mediated through the intervention of the federal regime, which strove to provide a "Square Deal"—which Roosevelt took as the motto for his administration—to both sides. The settlement was an important step in the Progressive era reforms of the decade that followed. There were no more than major coal strikes until the 1920s.[28]

See too [edit]

- History of coal miners

- History of coal mining

- History of coal mining in the Usa

- Lackawanna County Courthouse and John Mitchell Monument

- Listing of worker deaths in United States labor disputes

- Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt

References [edit]

- ^ "The Bully Black coal Strike of 1902". Archived from the original on 2008-06-21. Retrieved 2008-07-xiv .

- ^ "Archived re-create". Archived from the original on 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2012-06-16 .

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy equally title (link) - ^ Blatz 1991

- ^ Robert J. Cornell, The Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902 (1957) p 45

- ^ Edmund Morris, Theodore Rex (2001) p. 133

- ^ Dubofsky, Melvyn, and McCartin, Joseph A.. Labor in America : A History. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2017. Accessed September 8, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Primal.

- ^ Edmund Morris, Theodore Rex 2001 p. 134

- ^ H. Due west. Brands, T. R.: The Last Romantic (1998) p. 457

- ^ Herbert Croly, Marcus Alonzo Hanna (1912) p. 399

- ^ a b Henry F. Pringle, Theodore Roosevelt: A Biography (2002) p, 190

- ^ Frederick Saward and Sydney A. Unhurt, The Coal Trade (1920) p. 71

- ^ "Theodore Roosevelt, a Civil War Full general, and the Battle for Labor Peace" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-04-29. Retrieved 2018-04-29 .

- ^ Autobiography of Theodore Roosevelt

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt and His Times: A Chronicle of the Progressive Move

- ^ The role of federal military forces in domestic disorders, 1877-1945

- ^ Jean Strouse, Morgan: American Financier (2000) pp 449-51

- ^ James Ford Rhodes, The McKinley and Roosevelt Administrations, 1897-1909 (1922) p 246

- ^ Walter T. K. Nugent, Progressivism: A Very Short Introduction (2010) p. 38

- ^ John A. Farrell, Clarence Darrow: Attorney for the Damned (2011) p, 116

- ^ Wiebe, 1961, p 249-51

- ^ Mitchell, John (1903). Organized labor; its problems, purposes, and ideals and the present and hereafter of American wage earners. American Volume and Bible House. p. 322.

- ^ Roy, Andrew (1907). A History of the Coal Miners of the Usa, from the Evolution of the Mines to the Close of the Anthracite Strike of 1902. Press of J. L. Trauger printing Company. p. 4000.

- ^ "Striker Shot Dead by Constabulary". Daily News from Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania. July 2, 1902. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "The Iron Historic period". No. vol. 70, folio 45. Chilton Company. Baronial 7, 1902.

- ^ "Trigger-happy Fighting in Streets". No. 301. Los Angeles Herald. 31 July 1902. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "Soldier Kills a Striker". The Rock Island Argus, Volume 51, Number 303. nine October 1902. p. one. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ PHMC: Governors of Pennsylvania Archived August 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wiebe 1961

Bibliography [edit]

- Akin, William Due east. "The Cosmic Church and Unionism, 1886-1902: A Study of Institutional Aligning." Studies in History and Social club. 3:1 (1970): xiv-24.

- Aurand, Harold W. Coalcracker Culture: Work and Values in Pennsylvania Anthracite, 1835-1935. Selinsgrove, Pa.: Susquehanna University Press, 2003. ISBN 1-57591-064-0

- Blatz, Perry One thousand. Democratic Miners: Work and Labor Relations in the Anthracite Coal Manufacture, 1875-1925. Albany, N.Y.: Country Academy of New York Printing, 1994. ISBN 0-7914-1819-7

- Blatz, Perry K. "Local Leadership and Local Militancy: The Nanticoke Strike of 1899 and the Roots of Unionization in the Northern Anthracite Fields." Pennsylvania History. 58:4 (October 1991): 278-297.

- Cornell, Robert J. The Black coal Strike of 1902 (1957)

- Flim-flam, Mayor. United We Stand: The United Mine Workers of America 1890-1990 (UMW 1990), pp 89–101 semiofficial union history

- George, J.E. "The Coal Miners' Strike of 1897," Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 12, No. two (January., 1898), pp. 186–208 in JSTOR

- Gowaskie, Joe. "John Mitchell and the Anthracite Mine Workers: Leadership Conservatism and Rank-and-File Militancy." Labor History. 27:1 (1985–1986): 54-83.

- Greene, Victor R. "A Report in Slavs, Strikes and Unions: The Anthracite Strike of 1897." Pennsylvania History. 31:ii (April 1964): 199-215.

- Grossman, Jonathan. "The Coal Strike of 1902 – Turning Point in U.S. Policy." Monthly Labor Review. October 1975. Bachelor online.

- Harbaugh, William. The Life and Times of Theodore Roosevelt. (2nd ed. 1963)

- Janosov, Robert A., et al. The Smashing Strike: Perspectives on the 1902 Anthracite Coal Strike. Easton, Pa.: Canal History and Technology Press, 2002. ISBN 0-930973-28-3

- Morris, Edmund. Theodore King. (Random Firm, 2001). ISBN 0-394-55509-0; biography of TR equally President

- Perry, Peter R. "Theodore Roosevelt and the labor movement" (MA thesis California Land University, Hayward; 1991) online; ch 1 on strike.

- Phelan, Craig. "The Making of a Labor Leader: John Mitchell and the Anthracite Strike of 1900." Pennsylvania History. 63:ane (January 1996): 53-77.

- Phelan, Craig. Divided Loyalties: The Public and Private Life of Labor Leader John Mitchell. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Printing, 1994. ISBN 0-7914-2087-six

- Virtue, George O. "The Anthracite Miners' Strike of 1900," Periodical of Political Economy, vol. 9, no. 1 (Dec. 1900), pp. one–23. online free in JSTOR.

- Warne, Frank Julian. "The Anthracite coal Strike." Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (1901) 17#1 pp 15–52. online gratis in JSTOR

- Wiebe, Robert H. "The Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902: A Record of Defoliation." Mississippi Valley Historical Review. September 1961, pp. 229–51. in JSTOR

- Wilson, Susan E. "President Theodore Roosevelt's Role in the Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902." Labor's Heritage. 3:ane (1991): 4-2.

Primary sources [edit]

- Us Black coal Strike Committee, Study to the President on the Anthracite coal Strike of May–October, 1902 online edition

Music [edit]

- Byrne, Jerry, and George Gershon Korson. On Johnny Mitchell'southward Train. Library of Congress, 1947. Audio. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200197134/.

External links [edit]

- Department of Labor essay on the strike

- History of the 1902 strike

- A history of the coal miners of the Usa, from the evolution of the mines to the close of the anthracite strike of 1902 Cornell University Library Historical Monographs Collection.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coal_strike_of_1902

0 Response to "what step did rosevelt take to deal with the 1902 coal strike"

Post a Comment